Incident details

- Date of incident

- August 27, 2025

- Location

- Santa Ana, California

- Targets

- Ben Camacho (The Southlander)

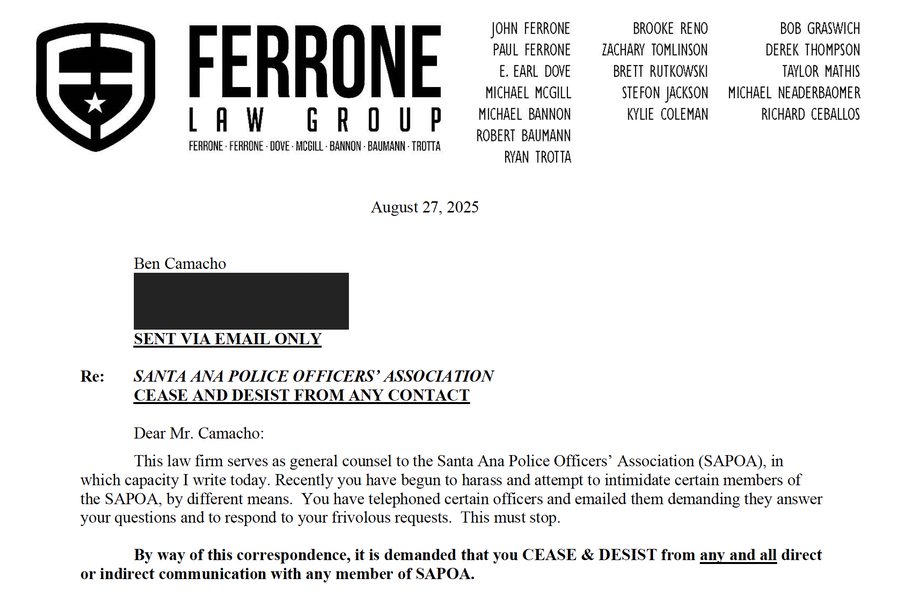

Attorneys for the Santa Ana Police Officers’ Association in California sent a cease and desist letter to investigative reporter Ben Camacho on Aug. 27, 2025, alleging that he had harassed various officers when he attempted to contact them.

Ben Camacho, an investigative reporter and co-founder of The Southlander, was ordered to stop reaching out for comment from police officers in Santa Ana, California, in a cease and desist letter sent by the city’s police union on Aug. 27, 2025.

Camacho told the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker that he is one of the few journalists who has done investigative reporting on the Santa Ana Police Officers’ Association and has written numerous articles critical of the police department.

When he received the email from the union, Camacho said, “I just kind of immediately laughed at it and then sent it to my attorneys.”

The letter, reviewed by the Tracker, alleged that Camacho had “begun to harass and attempt to intimidate certain members of the SAPOA,” but did not identify affected officers nor specific instances of the unacceptable conduct.

“You have telephoned certain officers and emailed them demanding they answer your questions and to respond to your frivolous requests,” it continued. “This must stop.”

Camacho said that, while he doesn’t know for sure what prompted the letter, he had worked on several recent stories involving two Santa Ana Police Department officers who are under investigation by the California Attorney General’s Office for their shooting of an unarmed individual in December 2024.

“As I continued to look into the officers involved, I later learned that one of those officers, one month after killing one person, he was involved in another incident where he shot and killed somebody, although this person had a knife. Still, a police shooting,” Camacho said. “That sparked my interest because it surprised me that he’s under investigation, yet he’s still on active duty.”

After going through his normal reporting process, Camacho said he published an article about the back-to-back shootings in June 2025. Later that month, the same officer was also involved in the beating of an unarmed teenager.

Camacho told the Tracker he was able to obtain a copy of an incident report through public records requests, and reached out to the officer in June through his city email address.

“I emailed him once or twice, just to see if he would comment. And then I ended up just sending him my questions after not hearing back, on just the off chance that he later wants to reply,” he said.

Camacho reached out for comment again at the beginning of August, after the family of the victim shot by police in December 2024 announced its plans to file a federal lawsuit against the two officers, as well as the city.

“I didn’t hear back. I think I emailed them once more the next day. In that email, I indicated to the one that I did have a phone for, that ‘I’m going to call you in about an hour if I don’t hear back, it’s just because I’m on deadline. Keep an eye out for my number in the signature and let me know if you are refusing to comment.”

The officer answered when he called, Camacho said, but after he identified himself and said he was a reporter for Caló News — the outlet he was on assignment for that day — the call abruptly ended.

“I didn’t know if it was a call drop or if he hung up, so I gave him the benefit of the doubt and called back, but then it went straight to voicemail,” he told the Tracker.

Camacho said he went through a similar process trying to contact a third officer involved in a traffic stop at issue in a lawsuit quickly settled by the city in July.

“The cease and desist doesn’t specify who or what or when or where, but of recent interactions, those are the three,” he said.

In a letter to the police union in response, Camacho’s attorney Shakeer Rahman wrote that its demands were “ridiculous.”

“There is no lawful basis to gag a person from ever communicating with government officials, let alone from communicating with an entire police force. That would be unconstitutional,” Rahman wrote. “And it is a bedrock journalistic practice to offer a person an opportunity to comment on forthcoming news reporting about them.”

Camacho told the Tracker that it was a clear attempt to stop him from continuing to report on the police department entirely.

“They’re framing journalism as a criminal act,” he said. “They’re framing my reasonable efforts to reach someone and make sure that they truly have a chance to comment or answer questions as a criminal act. That is not just anti-First Amendment, that is anti-democracy. And I think it’s a symptom of a larger problem we’re seeing right now under the rise of really harsh authoritarianism.

“But this is not my first rodeo, I’ve dealt with bigger fish,” he added, referring to a pair of lawsuits filed against him by the city of Los Angeles.

The Santa Ana Police Officers’ Association did not respond to a request for comment.

The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker catalogs press freedom violations in the United States. Email tips to [email protected].